Asia Times | 7 February 2018

Beijing plans new mechanism for Belt and Road arbitration

by Sabena Siddiqui

In a proactive move, China has plans under way to provide its own arbitration in any future commercial issues or disputes between the Belt and Road countries. The 68 countries and regions included in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) not only vary in economic strength but also require a stable trade environment with adequate legal safeguards.

To avert avoidable delays, providing a streamlined, cost-efficient dispute-settlement mechanism through China’s judicial and arbitration system is being planned to provide services for both Chinese and foreign parties.

Requiring considerable expansion, establishing arbitration institutions all along the New Silk Roads may not be easy but it would immensely enhance business credibility and ensure smooth project operations.

Usually mediation allows for an informal out-of-court settlement, while arbitration is more of a decisive alternative dispute resolution, and the last option is litigation, which is a formal court-based process.

Up until now transnational arbitration has been carried out under the New York Convention, based on the common law of the United States and Europe. In the beginning Chinese institutions may have to observe the international pattern for easier adaptability.

Wang Yiwei, director of the Institute of International Affairs, Renmin University, is optimistic. “China’s new international mechanism would better serve participating countries,” he says, as the current system to solve disputes was “complicated, time-consuming and costly” because it applied laws from Western countries and uses English as the common language.

Three specialized courts in China

Appropriate guidelines for establishing an arbitration mechanism were recently determined at a meeting of the Leading Group for Deepening Overall Reform of the 19th Communist Party of China Central Committee. Based in Xian, Shenzhen and Beijing, there would be three international commercial courts under the auspices of the Supreme People’s Court.

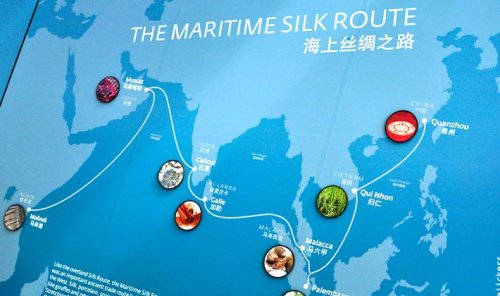

Commercial land-based disputes would be dealt with in Xian, while sea-route cases arising on the 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road would be covered in Shenzhen, while Beijing would be the headquarters of these BRI courts.

Working on the principles of wide consultation, joint contribution and shared benefits, these courts would function on the basis of the Chinese legal system while integrating international arbitration practices and providing for the equal legal protection of both Chinese and foreign parties’ rights.

Having assessed the situation, the China Council for Promotion of International Trade plans to create a non-governmental international organization with the assistance of various international commercial organizations.

In the beginning, Chinese legal professionals would work at these organizations to gain experience and learn the modalities in international arbitration. Achieving suitable expertise and perfection would require some time, specially as the BRI arbitration system has to provide for many countries.

As explained by Bai Ming, a research fellow with the Chinese Academy of International Trade and Economic Cooperation, “Building a dispute mechanism was difficult, as many countries that joined the initiative have different legal systems, social and cultural backgrounds.”

Lacking relevance regarding BRI land-based disputes in particular, a major handicap of the international arbitration system remains that it is mostly based on maritime law. Also in most cases, litigation in international commercial disputes becomes costly and time consuming and a mega-project like the BRI would be better off with a faster and more affordable trade arbitration mechanism already in place.

Complex rules, high costs

Resolution of disputes requires long-drawn-out mediation or arbitration, while enforcement is carried out under rules of cross-retaliation provided by the World Trade Organization according to the Understanding on Rules and Procedures Governing the Settlement of Disputes.

Lacking sufficient impact and effectiveness, especially if a developing country has a dispute with a developed country, the present system could do with a lot of improvement in any case. All this also costs a pretty penny – the fee per case is at least US$500,000 as charged by one of the well-known global arbitration institutions, the International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID). Quite understandably, such costs might be unaffordable for many developing countries.

Spanning the continents of Asia, Europe and Africa, establishing the new mechanism will be no small feat, and critics are quite unsure about the exact applications for now. Chris Devonshire-Ellis of Dezan Shira and Associates opines, “It is uncertain how much the legal authority of China is expected by Beijing to influence disputes, which by their cross-border nature are also bound by other nations’ sovereign laws.”

Giving an idea as to the practicability on ground, similar courts like the International Finance Center Courts in Dubai and the International Commercial Court in Singapore already have cooperative agreements with China.

As business expands along the new Silk Roads, legalities will require expert attention. Keeping this in mind, the Department of Justice in Hong Kong is also completing an online platform called the Belt and Road Arbitration and Mediation Initiative for dispute resolution in mass infrastructure projects.

Such facilities are the need of the hour, and Sarah Grimmer of the Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre says Beijing’s move is “a positive development” that reflects China’s foresight.