EJIL: Talk! | February 17, 2021

UNCITRAL and ISDS reform (online): Crossing the chasm

by Anthea Roberts and Taylor St. John

To text or not to text? That is the question. Or, rather, that was the question at UNCITRAL when Working Group III resumed its deliberations online last week. The Working Group’s focus was structural reforms, first selection and appointment of permanent or fixed-term adjudicators, then an appellate mechanism. As readers of this series know well, states hold different substantive views about the desirability of structural reform and these differences came out clearly in their interventions. But the more significant question of the week was one of process: whether, despite these differences, the time had come to move to text in an effort to “cross the chasm” of developing reforms. During the week, that question was answered in the affirmative.

The movement toward “texting” was significant, though not unexpected. In a letter to delegates before the session, the Chair explained that the Working Group will be developing numerous reforms over the coming years that will be presented for review and approval by the Commission on a rolling basis. However, the expectation is that all reform options will be finalized for presentation to the General Assembly at the same time, at the end of the entire project (projected to be 2025). In the Chair’s words: “Nothing will be formally done, until everything is done.” Details of the plan, including the pattern of alternating between considering structural and non-structural reforms and the timeline for what is expected to be completed by when, can be found in the draft work plan.

Against this background, the Chair began the week by explaining that it was time to put the Working Group “on the path to finalizing reforms.” The Group had to “move beyond the point of simply stating high level principles and positions” and look forward “to the development and consideration of text.” That meant moving past delegations “simply reiterating old positions that we have all heard before” and instead finding compromises on text that would “work for the group multilaterally.” The Chair noted that developing these proposals would require additional work in informal sessions between Working Group meetings, though any reforms would need to be decided in the main Working Group. This movement to text would require the “constructive participation of all states” though states could participate “completely without prejudice” to their final decision on which reforms to adopt.

The Chair’s exhortation was clear: it was time to text.

Not everyone was in favour. Some arbitration practitioners spoke often this week, making forceful, impassioned arguments against permanent appointments and an appellate mechanism. (As we describe in the next blog, we are seeing a fracturing of the arbitral community: some are actively opposing a permanent mechanism, others are voicing support, most—including all major arbitral institutions—are not expressing a position.) In a slightly more muted way, states that support the current system of ad hoc appointments warned against the dangers of jettisoning this in favor of a court system that was not—like arbitration—tried and tested through decades of experience. To those states, moving to text was premature. There were still objections at the level of principle, they argued, and insufficient agreement to consider text relating to structural reforms.

The European Union and its Member States, along with Switzerland, took a different view. These actors, which champion structural reform including an appeals mechanism and court of first instance, want to start developing and reviewing texts. They proposed developing text on these structural reforms in informal sessions and with the UNCITRAL Secretariat before bringing it back into the wider Working Group (they did not object to developing text on non-structural reforms too, but those were not under discussion this session). The time had come to move from generalities to specifics, from principles to text, they declared.

Most states sat somewhere in between these two poles and were pragmatic in their approach—they reserved their ultimate position about whether they supported a permanent mechanism, and instead raised specific concerns that they wanted to see addressed if such a mechanism were to be created. For instance, Brazil sought to ensure that the architecture of a permanent mechanism would accommodate state-state as well as investor-state disputes. Colombia emphasized that investors should not participate in consultative or selection committees for appointments, since investors were already represented by their countries of origin. Kenya observed that appointments should be made by parties to an investment treaty and that best efforts to ensure diversity should be made. Korea argued that the qualifications required for appointments to an appellate mechanism should be higher than those for a first-instance body, to ensure the legitimacy of the appellate mechanism. There seemed to be more enthusiasm generally for an appellate mechanism than permanent appointments at the first instance level, though the possiblity of rosters received more attention and support than previously.

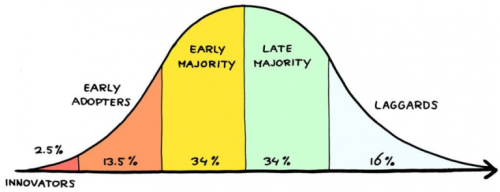

Why is this disagreement about whether to move to text significant? To understand this, it is helpful to see it through the “diffusion of innovation” and “crossing the chasm” theories developed by E.M. Rogers in 1962 and Geoffrey A. Moore in 1991 respectively.

The diffusion of innovation theory explains how, over time, an idea or product gains momentum and diffuses through a specific population or social system. Adoption of a new idea, product, or approach does not happen simultaneously. Instead, people who adopt an innovation early have different characteristics than people who adopt an innovation later. This means that different strategies are important when seeking to win over different groups of potential adopters. Based on Rogers’s research, there are five groups to consider:

- These are people who want to be first to adopt the innovation. They are prepared to jettison the old in favour of the new. Very little needs to be done to convince them to adopt the innovation.

- Early Adopters. These are people who are not the first to adopt the innovation, but jump to adopt relatively early and then seek to be opinion leaders in promoting the innovation.

- Early Majority. These people adopt new ideas before the average person, but they don’t move out too far ahead of the pack. Importantly, they often want to see more details and more evidence that the innovation will work in practice before they are willing to adopt it.

- Late Majority. These people tend to be sceptical about change and will only adopt an innovation after it has been tried and approved by the majority. Here, marketers are advised to inform people in this group about how many other people have tried the new innovation and liked it. The key to this group isn’t to get out in front, but it is to not be left behind as the general practice changes.

- These people are sceptical about the innovation; they tend to be bound by tradition and conservative about change. This group is unlikely to adopt at all or if they adopt will do so late in the process once they feel that there is no real alternative.

Now, of course, this theory cannot be transplanted directly into the UNCITRAL context. A state’s view on a particular innovation may be shaped more by its views on the efficacy of that innovation than by their general disposition as an innovator or “laggard” (we note that the latter is Rogers’s terminology, not ours, and many states would object—quite understandably—to it in this context). This theory also applies to technological innovations that have been widely adopted, whereas there is nothing inevitable here about which reforms will be adopted in the UNCITRAL context or how widely they will end up diffusing.

Yet since this reform process is likely to generate many reform “products” and states can choose which to join as well as continue to join over time, diffusion may provide a helpful way to think about ISDS reform dynamics. Each reform product may diffuse at a different speed. A given state may count as an early adopter with respect to one reform and a sceptic with respect to another. The EU and its Member States, for instance, are innovators when it comes to a permanent mechanism, but may be late majority actors or sceptics on some other reforms. Chile, Colombia, and Australia are innovators with regard to the design of an overarching instrument; Thailand is an innovator with regard to an advisory center; South Africa and Morocco are innovators when it comes to addressing third-party funding. Yet these states may be majority actors or sceptics on other reforms.

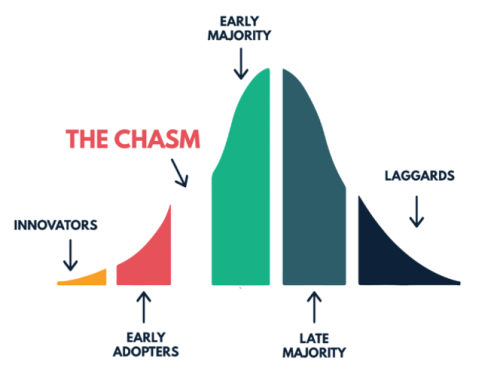

Even if the actors may be different, there are common patterns we are likely to observe as the various products diffuse. Moore argues that there is often a chasm between the early adopters of the product (the “visionaries,” in his language) and the early majority (the “pragmatists”). The visionaries believe in the innovation as a matter of principle. They are happy to adopt a rough prototype and then smooth out the details later, correcting problems and adopting upgrades as they go. The pragmatists are quite different. To get them on board, marketers need to develop a fully worked up product and make the pragmatists feel comfortable that the innovation will actually work and be an improvement. This cannot be done at the level of principle—it has to be done by putting the principles into practice.

That is where the “to text or not to text” debate becomes important. Although most of the airtime at UNCITRAL is taken up between the proponents and opponents of a particular innovation, that is a bit like seeing a fight between the two tails of this diffusion curve. Most states sit in the middle as the comparatively silent majority. If an innovation is going to gain support, these are the states that need to be brought on board. And they are unlikely to accept or reject an innovation based on principle alone. Text is important so that these states can see in detail WHAT is being proposed and HOW it might work. Evidence from small scale experiments—like the reforms states are adopting in different bilateral treaties—are also significant in showing what does and does not work in practice.

UNCITRAL working groups tend to move toward greater specificity as they progress, fleshing out model laws or reforms before states choose to adopt them or not. But as we have seen before, procedures that were uncontroversial in previous working groups can lead to contestation in Working Group III. And the move to texting can raise concerns that certain reforms might take on an air of inevitability, even if there is disagreement over them.

On Wednesday morning, the Chair explained his view that it was important to move to text, even if not all states agreed with all of the proposals. One of the things he enjoyed about the Working Group, he said, was the use of colourful idioms and analogies to explain positions, referencing the Russian Federation’s observation that being asked to work on permanent appointments was like being asked to dive head first into a pool that was not deep enough and hitting your head. Actually, the Chair countered, the pool has yet to be designed, let alone constructed and filled with water. He continued:

“ We are standing still on solid ground, hearing about where a pool might go, and what its design might be, but some delegations are saying already that it will be too shallow. And then when the builder suggests otherwise, and offers to draw it out, to design it, there are those who are saying we should simply say no and instead continue in our assumption that we were right without even looking at the plans.”

The Chair noted that a number of delegations had suggested that there are many outstanding questions. True, he noted, but that was not surprising:

“ This is exactly why I have proposed the way forward I have for all of our reform options — the way we get the answers that will allow delegations to actually make informed decisions is we do the work, we draft the text. It cannot be the way forward to say that something won’t work, there are too many questions, and then to refuse to allow the drafting work to go on that might answer those very questions.”

It was time to text. And while some states continued to note that they believed moving to text was premature—or to ask why it was okay to move to text now but hadn’t been last year when some states suggested intersessional work on a multilateral instrument—most seemed to embrace the move toward discussing text. On the whole, the tone of the week became more pragmatic and less polemical.

The next issue, we suppose, will be a more intense focus on WHO texts as well as HOW and WHEN that texting occurs. Who is going to hold the pen in drafting text? In what order will draft text on the various reforms emerge? What work will be done in intersessional meetings and what will be done by the Working Group as a whole? And what role might non-state observers play in these more informal processes?

We do not know which reforms will eventually be approved. Time will also tell which of these reforms end up diffusing widely. But this week was significant: in deciding to make the move to text on all of the main proposals, the Working Group made its first step toward crossing the chasm.