All the versions of this article: [English] [Español]

by Luciana Ghiotto | 29 October 2024

Honduras against the corporate Goliath

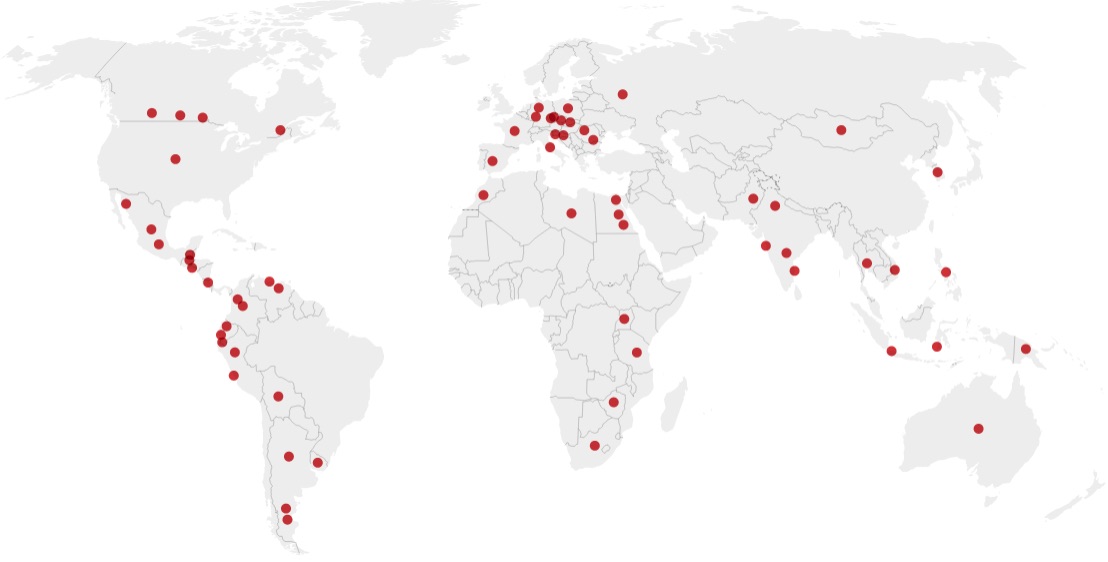

On 21 September 2024, we concluded our tour of departments and territories across Honduras to present the report ‘The corporate assault on Honduras: Mafia-style investments and the Honduran people´s struggle for democracy and dignity’. 1 This report was the outcome of our research at the Transnational Institute (TNI) together with the Institute for Policy Studies (IPS) in the US, TerraJusta (based in Bolivia) and the Honduras Solidarity Network (based in Canada and the US). After a year of interviews, conversations and debates, our 130-page report presented basic information on the 14 arbitration claims against Honduras from 2023 to mid-2024, in addition to five earlier claims.

Many Latin American countries have received claims from foreign investors: up to September 2024, 380 have been filed.2 Honduras is a special case, however: the original ‘banana republic’, it has long been referred to as a ‘forgotten country’ According to official data, more than half of the Honduran population lives in poverty and 44% works in the informal economy;3 710,00 people are non-literate (12% of the adult population, and up to 18% in rural areas).4 Although not at war, Honduras has become one of the world’s most violent countries (violence perpetrated by transnational criminal organisations, local drug-trafficking groups, and gangs, often in collusion with local politicians).5 To escape this violence and poverty, 10% of Honduran citizens have emigrated, many in the unsafe so-called migrant caravans walking towards the US border. By August 2024, the country had received US$ 6 billion in remittances, which represents 25% of its gross domestic product (GDP),6 but the country’s wealth is largely concentrated in 17 families, linked in many cases to corruption and drug-trafficking networks.

At the same, the growth of the maquila industry (assembly plants) since the late 1970s has resulted in Honduras becoming one of the 10 largest textile suppliers to the US. On the outskirts of San Pedro Sula, the country’s second city in the lowland northern region where 80% of Honduran maquilas are concentrated, a sign emblazoned on a hill says ‘To export is to progress’. An industry that invests billions of dollars in manufacturing, but where the minimum monthly wage for hundreds of workers – mainly young women – is close to US$ 4507 in a labour regime where production goals of 6,000 items a day must be met.8

An avalanche of lawsuits against Honduras

This small and impoverished Central American country received 14 lawsuits in international arbitration between 2023 and 2024, becoming the second most sued country in Latin America in the same period after Mexico. Our report, which was completed in September 2024, examined the four claims that were filed at the International Centre for the Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) during the month of August, when the departure from this organisation announced by the President Xiomara Castro in February 2024 became effective.

Various elements characterise these lawsuits. First, many of the investments were made irregularly during the period known as the narco-dictatorship in Honduras, following the 2009 coup d’état that overthrew president Manuel Zelaya (known as MEL). Most of these investments were riddled with corrupt administrative practices, and were imposed against the will of local populations under the repressive government of Juan Orlando Hernández (known as JOH) from 2014 to 2022. In several of these lawsuits, investors had direct or indirect links to criminal and drug-trafficking networks.

Seven claims were also filed against the efforts of Castro’s government to renegotiate contracts on the cost of electricity, of which just five of these investors demand more than US$ 1.3 billion.

A country like Honduras seems to have no right to criticise the investment protection system, where legal security for investors is expected to prevail over any other factor, such as the will of entire communities and their constitutional right to live in a healthy environment. The Castro government’s decision to withdraw from ICSID was heavily criticised by right-wing politicians and business sectors, who described it as ‘economic self-sabotage’.9

Honduras_investment_protection

Próspera, the most notorious arbitration claim

The most notorious claim against Honduras is undoubtedly that of Próspera. This US business group is demanding almost US$ 11 billion, equivalent to almost three times the country’s 2024 Public Investment Plan. The demand is based on the government’s 2023 review of the ZEDEs (Zones of Employment and Economic Development), after identifying various irregularities in the approval of the reforms to facilitate their creation between 2012 and 2013. It is because of these irregularities that the Castro government has called the ZEDEs ‘an act of public–private corruption’ that led to the transfer of state sovereignty to private investors.

Próspera’s attack strategy on the government’s decision to review the ZEDEs has been intelligent: its lawyers, the firm White & Case, argue that both the Investment chapter of CAFTA-DR has been violated, and also that of an Agreement for Legal Stability and Investor Protection (LSA), which was secretly negotiated with the state and to which we do not have access. Its clauses and specific commitments are unknown. Próspera maintains in its official communications that ‘the ZEDE framework was specifically designed and adapted to guarantee legal certainty, and the ZEDE framework provides for multiple layers of guarantees of legal stability at all levels of the law’. As always, transparency is conspicuous by its absence in this system, which is tilted in the companies’ favour.

Certainly, the case has raised a few eyebrows: a financial group has taken advantage of a country experiencing institutional turbulence and legislation that benefits it with the aim of creating a libertarian model city on Roatán, a Caribbean paradise island. An attempt to replicate tiny Singapore, but in Central America. It is obviously no coincidence that the ZEDE Próspera was strategically located in Roatán, where it is difficult to mobilise anyone, whether police forces or popular demonstrations.

Clearly, this mega-demand has attracted the attention of the international press and of US social and political organisations. Its implications have led US senators to demand that the Biden Administration remove the arbitration mechanism from US treaties, since they include the legal mechanism that enables this type of claims.10

While Próspera has become particularly high-profile case, there are many other relevant claims against Honduras. All the recent arbitration claims, covering various economic sectors and the origin of the investors, highlight the country’s institutional fragility, where decisions are made by politicians addicted to power and in collusion with economic groups. A third of the claims filed since 2023 relate to investments that have generated local resistance.

For example, the ZEDEs sparked community resistance in Crawfish Rock in Roatán and at the national level due to their significance for the entire country. In November 2023, the National Meeting of Resistance against the ZEDEs organised by popular organisations denounced the fact that these have increased their territorial expropriation. The claims in the arbitration also involve community resistance against energy projects such as Los Prados in the southern department of Choluteca, where the installation of solar panels caused the displacement of residents and various effects on health and the environment. The cost of local rejection was persecution and criminalisation of local leaders. Norwegian companies had invested in this project , including a public ‘development’ fund, such as Norfund, which presents itself as ‘an investor in development that creates jobs and supports the transition to zero emissions’.11 But so that Honduras can announce that it is diversifying its energy mix and moving towards sustainable energies, regions are sacrificed, and land use is changed. As the local population argues, instead of producing food for an impoverished population, the land now produces photovoltaic panels. This case shows that behind the discourse of energy transition are hidden the dirtiest effects in some of the world’s poorest countries.

Honduras_investment_protection

Claims associated with an enclave economy

Several arbitral claims against Honduras arise from its character as an enclave economy. At least four of the claims relate to its specialisation in manufacturing for export. Even if at first glance these are isolated claims, these investments contribute to deepening and expanding the export economy, and are not intended to benefit local populations. We look briefly at investments in 1) toll roads; 2) housing for maquila workers; and 3) port infrastructure.

The lawsuit related to the road infrastructure and installation of toll booths was filed by the company Autopistas del Atlántico, a Colombian and Honduran consortium (plus the participation of Chilean, Costa Rican and Panamanian capital) that was financed by the huge US banks Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan Chase. The project in question is the El Progreso–San Pedro Sula corridor, an area producing bananas and other produce for foreign companies such as the United Fruit Company Dole plc and Chiquita Brands International. Autopistas claimed that its contract was violated when the toll road was suspended following local protests and its subsequent cancellation in 2018. An attempt was made to install toll booths on that route, which was resisted by the residents of El Progreso for more than a year. A camp was set up in front of the booths where it was explained that tolls violated the right to free movement, since there was no alternative route, and that the road had been built using public tax revenues. Local people feared that these tolls would increase the cost of food that arrived by truck, which would have a direct impact on households. Finally, and even after it was proved that there had been numerous irregularities in the signing of the contract, the company filed a claim for US$ 179 million at the ICSID in April 2023.

A second claim arising from the enclave economy is related to housing for maquila workers in the Sula Valley, where the maquiladoras are located, often in Special Economic Zones (SEZs). The brothers Ernesto and Juan Carlos Argüello, based in Miami, promised to create ‘model towns’ – decent houses, security, green areas and other services – the reality is that hurricanes Eta and Iota that struck the country in 2020 showed the fragility of the infrastructure, the absence of contingency plans and the lack of response regarding the insurance policies. According to local residents, the investors did not even begin repairing the damage. The entire investment had been a farce: the houses turned out to be of poor quality and the promised services never materialised. For these reasons, local people gathered at the Patronato del Residencial Castaños de Choloma decided to stop paying the instalments, demanding responses from the investors and upholding their right to decent housing. Yet the brothers sued Honduras for US$ 100 million (plus US$ 2 million for ‘moral damages’).

The third group of claims associated with the export economic model are presented by two operators of Puerto Cortés. Operadora Portuaria Centroamericana (OPC) of Honduras and the Philippine company Servicios de Terminal de Contenedores Internacionales (which manages OPC) presented their claims to the ICSID in August 2024, days before Honduras’ departure from this arbitration institution was made official (and there is still no information on the amounts claimed). These companies operate containers in the largest port in Honduras, located on its Caribbean coast, and only 60 km from the maquila area in San Pedro Sula. Almost all of the country’s imports and exports, including manufactured goods and agricultural produce, pass through Puerto Cortés.12There is no concrete information on the reasons why these lawsuits were filed, except for allegations that ‘the Republic of Honduras has violated certain obligations’ of the signed contract.13 Once again, the opacity of the system is obvious.

As we can see, these arbitration claims are not just a legal matter. They are a deep political issue, which puts the export-led economic model at the centre of the debate. Discussing arbitration claims is not just about the astronomical amounts claimed by investors, but also shows how deep poverty is sustained in countries like Honduras, sadly destined to sustain precarious and low-cost jobs to produce the manufactured goods consumed in rich countries. In this sense, the country’s withdrawal from ICSID, even if it was a brave decision, is not enough, especially given that trade and investment protection treaties have deepened an economic model for exports and for big capital, and not for local populations. The forgotten country shows us the need to revive a discussion on the international division of labour and, with it, its trade and investment treaties.

Notes

- Transnational Institute (TNI): ISDS in numbers. www.isds-americalatina.org (external link)

- Ministerio de Trabajo y Seguridad Social de Honduras. Boletín Estadístico: Empleo informal, 2022. https://www.trabajo.gob.hn/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/BOLETIN-EMPLEO-INFORMAL_2022-.pdf (external link)

- Otras voces en educación. https://otrasvoceseneducacion.org/archivos/405480 (external link)

- Insight Crime. https://insightcrime.org/es/investigaciones/elites-crimen-organizado-honduras-introduccion-honduras/ (external link)

- La Prensa. https://www.laprensa.hn/honduras/honduras-recibio-6-mil-millones-dolares-remesas-NF21605796 (external link)

- El Heraldo. https://www.elheraldo.hn/economia/cuanto-aumento-salario-minimo-maquila-de-honduras-2024-a-2026-EM18142503 (external link)

- Criterio. https://criterio.hn/la-maquila-en-honduras-una-maquina-destructora-de-cuerpos/ (external link)

- Honduran Council of Private Corporations declaration on X (formerly Twitter), 4 March 2024. https://x.com/COHEPHonduras/status/1764712417018204529 (external link)

- Congress of the United States, Letter of 33 Senators to Ambassador Tai and Secretary Blinken, 2 May 2023. https://www.warren.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/2023.05.02%20Letter%20to%20Tai,%20Blinken%20re%20elimination%20of%20ISDS.pdf (external link)

- Norfund. https://www.norfund.no/ (external link)

- International Container Terminal Services. https://www.ictsi.com/our-offering/our-terminals/operadora-portuaria-centroamericana-sa-de-cv (external link)

- Securities and Exchange Commission. https://cdnweb.ictsi.com/s3fs-public/2024-08/International%20Centre%20for%20Settlement%20of%20Investment%20Disputes%20%28ICSID%29%20registers%20the%20arbitration%20requested%20by%20ICTSI%20and%20OPCagainst%20the%20Republic%20of%20Honduras_0.pdf (external link)